|

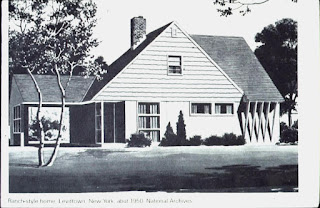

| You're better off with a small sunny house than a big one with lousy solar orientation. |

• Big Deal Number One: Solar Orientation. The crucial question that determines whether a house will be livable is one that's routinely overlooked in house-hunting—namely: “Where does the sun come in?” Abundant natural light is far more important than the kind of attributes that usually preoccupy home buyers, such as room size or interior finish. Natural light is the reason a sun-filled cottage can seem infinitely more appealing than an ostentatious house with a lot of dark rooms.

The rules of good solar orientation are simple: Major living areas should face south or nearly so; kitchens and breakfast rooms should face east to southeast; garages, secondary baths, and other service rooms should face north. Of course, not every house can meet this ideal—but the closer you come, the better.

|

| Look past the petunias the brokers planted yesterday and check out how things look beneath the surface. |

• Big Deal Number Two: Soundness of Structure. I’m always amazed to see buyers place such high value on fresh paint or carpets, while blithely overlooking glaring signs of structural trouble such as sloping floors or wracked doorways. It’s common for houses to receive a quick cosmetic makeover before they’re put on the market, but alas, superficial good looks don’t guarantee solid underpinnings. Learn to look past the fresh paint and hastily planted petunias to ensure that the home’s beauty is more than skin deep.

|

| Oh oh—this is something you probably don't want to see. Fresh paint won't make it go away. (Image courtesy of Barrie Home Inspector) |

See the ugly houses

on solid rock they stand

Come see my shining castle

that’s built upon the sand.

|

| Purple may not be your be thing, but don't rule out a solid, well-oriented house for such superficial shortcomings. It's just paint, and easily fixed. (Image courtesy of AllKitchenAppliances) |

Unfashionable colors or finishes in areas such as paint, carpets, or countertops; outdated hardware items such as faucets, appliances, or lighting fixtures; or the absence of garage-door openers, log-lighters, and other modern-day gimmicks. Outdated hardware and finishes can be easily upgraded at reasonable cost, and high-tech bells and whistles can always be added if it’s imperative. But who knows—with a sturdy, sun-filled house underfoot, you might just learn to live without them.