|

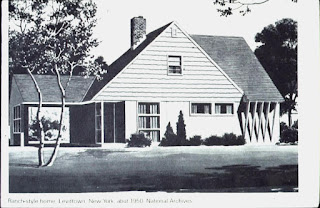

| In 1947, builder William Levitt got the postwar housing ball rolling with his first mass-produced tract at Levittown, New York. This is a later and more ornate example of a Levitt home of the 1940s. |

A half-century ago, in the gray no-man’s-land between the end of World War II and the heart of the Fabulous Fifties, there arose a humble little home style that’s been all but forgotten by three generations of buyers. For lack of a better name, we’ll call it the Postwar Tract. Over the span of barely a decade, it formed the stylistic bridge between the bolt-upright look of prewar homes and the racy, low-slung lines of the Rancher—a neat delineation in the change from prewar to postwar sensibilities.

|

| Typical 1940s-era elevation, with close-cropped roof overhangs, hip roof, and horizontal siding. |

Stylistically, the Postwar Tract made do with less. Walls were thinner, overhangs shorter, detailing sparse—perhaps a bit of a Depression Era/War Shortage hangover. No matter, the flamboyant Rancher would cure that a few years later.

How can you tell if you own a Postwar Tract, or are about to? If the house was built between 1945 and 1955, case closed. If you’re not sure, look for stucco or horizontal wood siding, or a combination of these, as an exterior finish. Inside, expect to see drywall or, in early cases, gypsum lath (as opposed to wood lath). Steel casement or wooden double-hung windows having only horizontal muntins (dividing bars) are another unmistakable trait. Hardwood flooring (possibly concealed by wall-to-wall carpet, single-panel doors, and a low-pitched hip or gable roof with composition shingles are three more easy clues.

|

| A larger, gable-roofed variant of the decade's aesthetic. Note the oh-so-skinny 4x4 porch columns. |

• Postwar Tract homes aren’t on anybody’s “hot” list—yet. Their spartan detailing and modest scale doesn’t garner the sort of press that Bungalows and Ranchers receive, and this anonymity in turn keeps sale prices relatively reasonable.

• The Postwar Tract floor plan, while not exactly roomy, is simple and practical. Many examples also have generously-sized windows and hence good daylighting—a trait that many earlier styles can’t lay claim to.

• Postwar Tracts are less susceptible to the plumbing and wiring infirmities that plague prewar homes with more primitive technology. In general, they also have better foundations than their predecessors.

Now, the bad news:

|

| Another hip-roofed version. This example features a common detail of the era, windows with horizontal mullions. |

• The small scale of the parts often extends to the whole house as a whole; there’s usually little room to spare, especially in kitchens, baths and closets. One bright spot: Postwar Tracts were built on very generous lots and are relatively easy to expand. So if room is scarce, you can always add more.

No comments:

Post a Comment