How would you like a committee deciding what clothes you could wear each day?

|

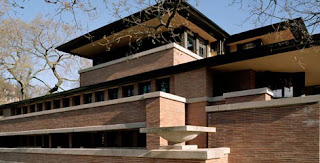

| Frank Lloyd Wright's famed Robie House of 1909: If design review boards had existed at the time, it would never have been built. |

A third would pipe in with, “We’d prefer to see a blue shirt, okay?”

There’s a similar institution in many of our city planning departments. It’s called a design review board, and it presumes to tell architects and homeowners what “clothes” their homes are allowed to wear. In many cities, design review is required whenever a set of residential plans is submitted for approval.

|

| Harry Oliver's Spadena House, Beverly Hills (1926): Would it pass the Design Review Board in your town? Not bloody likely. |

Design review is based on the shaky premise that a panel of city appointees can judge aesthetics better than anyone else, and should therefore have the final say on what your project should look like—more of a say, even, than you or your architect.

Beauty is a highly individual perception, however. What’s more, our judgment of aesthetics is inextricably rooted in the context of our own time. Architecture that we find ugly or shocking today may well be perfectly acceptable in twenty years. Conversely, the features design review boards love to see nowadays may be considered schlock in a few decades. You se always on shaky ground simply can’t presume to make airtight aesthetic judgments from the vantage point of the present.

|

| Bruce Goff's Bavinger House (Norman, Oklanhoma, 1955—now destroyed): Another non-starter if Design Review Boards had had anything to do with it. |

And as you might guess, design review boards are composed of ordinary humans with ordinary aesthetic prejudices. That’s why it’s so dangerous for them to decide what is “appropriate” design and what isn't.

|

| Frank Gehry's Venice, CA Beach House (1984): A Design Review Board might have approved this design—but only if Gehry had already been world famous. |

Right about here, I usually get this rejoinder: “So you’d let people build any old piece of junk, anywhere they want?”

Hardly. For well over a hundred years, cities have had a means of enforcing regulations affecting public health and safety, and rightly so. That instrument is the zoning code, and it’s the proper place for the city to wield its authority. It’s the zoning code, for example, that prevents your neighbor from building right up to your fence line, or locating a gunpowder factory next to your house. No one argues with the need to regulate matters of public safety.

But enforcing public safety is a very different thing from enforcing taste. A purple house doesn’t present any risk to the public. Or does it, design review officials? Responses are invited.

No comments:

Post a Comment